Serbia

| Republic of Serbia

Република Србија

Republika Srbija (Serbian) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Боже Правде / Bože Pravde |

||||||

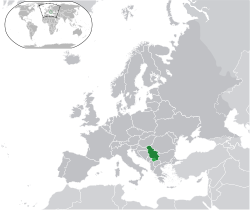

Location of Serbia (green) – Kosovo (light green)

on the European continent (dark grey) |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Belgrade |

|||||

| Official language(s) | Serbian1 | |||||

| Demonym | Serbian | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| - | President | Boris Tadić | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Mirko Cvetković | ||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | Statehood | 850 | ||||

| - | Raška Kingdom | 1217 | ||||

| - | Serbian Empire | 16 April 1346 | ||||

| - | Independence lost to Ottoman Empire | 20 June 14592 | ||||

| - | Serbian revolution | 15 February 1804 | ||||

| - | Independence recognized | 13 July 1878 | ||||

| - | Unification with Vojvodina | 25 November 19183 | ||||

| - | Independent state | 5 June 2006 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 88 361 km2 (incl. Kosovo)(113th) 34 116 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.13 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2009 estimate | 7,334,935[1] (excl. Kosovo) | ||||

| - | Density | 107,46/km2 (94th) 297/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $80.602 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $10,897[2] (excluding Kosovo) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | 43.662 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $5,898[2] (excluding Kosovo) | ||||

| Gini (2007) | .24 (low) | |||||

| HDI (2007) | 0.826 (high) (67th) | |||||

| Currency | Serbian dinar (RSD) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .rs | |||||

| Calling code | 381 | |||||

|

1 See also regional minority languages recognized by the ECRML.

2 Titular rulers of Serbia in Hungarian exile claimed Serbian throne until 1540.[3][4] Belgrade fell to Ottomans in 1521. Serbia was briefly reestablished by Jovan Nenad 1526–7. |

||||||

Serbia (pronounced: /ˈsɜrbiə/), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian: Република Србија, Republika Srbija), is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central- and Southeastern Europe, covering the southern lowlands of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans. Serbia borders Hungary to the north; Romania and Bulgaria to the east; the Republic of Macedonia to the south; and Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro to the west; its border with Albania is disputed. Serbia's capital city, Belgrade, is among the most populous in Southeastern Europe.

After their settlement in the Balkans, Serbs formed a medieval kingdom that evolved into a Serbian Empire, which reached its peak in the 14th century. By the 16th century Serbian lands were conquered and occupied by the Ottomans, at times interrupted by the Habsburgs. In the early 1800s, the Serbian revolution established the country as the region's first constitutional monarchy, which subsequently expanded its territory and pioneered the abolition of feudalism and serfdom in Southeastern Europe.[5][6] The former Habsburg crownland of Vojvodina joined Serbia in 1918. Decimated as a result of World War I, the country united with other South Slavic peoples into a Yugoslav state which would exist in several forms up until 2006, when Serbia once again became independent.

In February 2008, the parliament of Kosovo, Serbia's southern province with an ethnic Albanian majority, declared independence. The response from the international community has been mixed. Serbia regards Kosovo as a autonomous province, governed by UNMIK, a UN mission.

Serbia is a member of the United Nations, Council of Europe, BSEC, and will preside over the CEFTA in 2010. Serbia is classified as an emerging and developing economy by the International Monetary Fund and an upper-middle income economy by the World Bank.[7] WTO accession is expected in 2010.[8] Serbia has a high Human Development Index[9] and Freedom House in 2008 listed Serbia as one of few free Balkan states.[10] The country is also an EU membership applicant and a neutral country.[11][12]

History

Prehistory and early history

The Vinča and Starčevo cultures were early neolithic civilizations in Serbia between the 7th and the 3rd millennium BC. Many archeological sites show a long history of culture in Serbia, such as the Lepenski Vir.

The Paleo-Balkan peoples, such as the Thracians, Dacians, Illyrians were autochthonous inhabitants of Serbia prior to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC. Greeks expanded into the south of modern Serbia in the 4th century B.C., the northernmost point of the empire of Alexander the Great being the town of Kale-Krševica. The Celtic tribe of Scordisci settled in the 3rd century BC and built many fortifications such as the Kalemegdan fortress, and founded many modern cities in Serbia, such as Singidunum, the city that evolved into Belgrade, the capital of Serbia.

Contemporary Serbia extends fully or partially over several classical Roman provinces such as Moesia, Pannonia, Praevalitana, Dalmatia, Dacia and Macedonia. The northern Serbian city of Sirmium was one of the capitals of the Roman Empire during the Tetrarchy.[13] No less than 17 Roman Emperors were born in what is now Serbia, the most after present-day Italy.[14] The most famous Roman Emperor born in Serbia is Constantine I who empowered Christianity throughout the Roman Empire.

Medieval Serbia

The beginning of the Serbian state starts with the settling of the White Serbs in the Balkans led by the Unknown Archont, who was asked to defend the Byzantine frontiers from invading Avars. Emperor Heraclius granted the Serbs a permanent dominion in the Sclavinias of Western Balkans upon completing this task. By the 750's a great-grandson of the Unknown Archont- Prince Višeslav[16][17] managed to unite several territories, which led to the founding of Raška, which lay between the crisis-struck Byzantine and the growing Frankish Empire.[18][19]

At first heavily dependent on the Byzantine Empire as its vassal, Raška gained independence by the expulsion of the Byzantine troops and the major defeat of the Bulgarian army around 850 AD during the rule of Vlastimir of Serbia, the founder of the first Serbian dynasty, the House of Vlastimirović. The Christianization of the Serbs was complete in 867–869 when Byzantine Emperor Basil I sent priests after Knez Mutimir had acknowledged Byzantine suzerainty.[20] At about the same time, the western Serbs were subjugated to the Frankish Empire.[21] The First dynasty died out in 960 A.D; the wars of succession for the Serb throne led to Serbian incorporation into the Byzantine Empire in 971. Around 1040 AD, an uprising in the medieval state of Duklja overthrew Byzantine rule. Duklja then assumed dominion over the Serbian lands during the 11th and 12th centuries. In 1077 A.D., Duklja became the first Serb Kingdom [22] following the establishment of the Catholic Bishopric of Bar. From the late 12th century onwards, Raška rose to become the paramount Serb state. Over the 13th and 14th centuries, it ruled over the other Serb lands. During this time, Serbia began to expand eastward and southward into Kosovo and northern Macedonia and northward for the first time.

The Serbian Empire was proclaimed in 1346 by Stefan Dušan, during which time the country reached its territorial, spiritual and cultural peak, becoming one of the most powerful states in Europe.[23] Dušan's Code, a universal system of laws, was enacted. Dušan was succeeded by his son Uroš Nejaki, The Weak). Rather young and too incompetent to maintain a strong grip on the empire created by his father, he watched the Serbian Empire fragment into a conglomeration of principalities. Uroš died childless in December 1371, after much of the Serbian nobility had been destroyed by the Turks in the Battle of Maritsa earlier that year.

The Houses of Mrnjavčević, Lazarević and Branković ruled the Serbian lands in the 15th and 16th centuries. Constant struggles took place between various Serbian kingdoms and the Ottoman Empire. After the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 and the Siege of Belgrade, the Serbian Despotate fell in 1459 following the siege of the provisional capital of Smederevo. After repelling Ottoman attacks for over 70 years, Belgrade finally fell in 1521. Forceful conversion to Islam became imminent, especially in the southwest Raška, Kosovo and Bosnia. To the south, the Republic of Venice grew stronger in importance, gradually taking over the coastal areas.

Ottoman and Austrian rule

After the loss of independence to the Kingdom of Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, Serbia briefly regained sovereignty under Emperor Jovan Nenad in the 16th century. Three Austrian invasions and numerous rebellions, such as the Banat Uprising, constantly challenged Ottoman rule. Vojvodina endured a century long Ottoman occupation before being ceded to the Habsburg Empire in the 17th–18th centuries under the Treaty of Karlowitz. As the Great Serb Migrations depopulated most of Kosovo and Serbia proper, the Serbs sought refuge in the more prosperous Vojvodina in the north and Military Frontier in the West where they were granted imperial rights by the Austrian crown under measures such as the Statuta Wallachorum of 1630. The Ottoman persecutions of Christians culminated in the abolition and plunder of the Patriarchate of Peć in 1766.[24] As Ottoman rule in the Pashaluk of Belgrade grew ever more brutal, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I formally granted the Serbs the right to their autonomous crown land following several Serbian petitions such as the one from Timisoara.[25]

Serbian revolution and monarchy

The quest for national emancipation was first undertaken during the Serbian national revolution, in 1804 until 1815. The liberation war was followed by a period of formalization, negotiations and finally, the Constitutionalization, effectivelly ending the process in 1835.[26] For the first time in Ottoman history an entire Christian population had risen up against the Sultan.[27] The entrenchment of French troops in the western Balkans, the incessant political crises in the Ottoman Empire, the growing intensity of the Austro–Russian rivalry in the Balkans, the intermittent warfare which consumed the energies of French and Russian Empires and the outbreak of protracted hostilities between the Porte and Russia are but a few of the major international developments which directly or indirectly influenced the course of the Serbian revolt.[27]

During the First Serbian Uprising, or the first phase of the revolt, led by Karađorđe Petrović, Serbia was independent for almost a decade before the Ottoman army was able to reoccupy the country. Shortly after this, the Second Serbian Uprising began. Led by Miloš Obrenović, it ended in 1815 with a compromise between the Serbian revolutionary army and the Ottoman authorities. German historian Leopold von Ranke published his book "The Serbian revolution" in 1829.[28] They were the easternmost bourgeois revolutions in the 19th-century world.[29] Likewise, the Principality of Serbia was second in Europe, after France, to abolish feudalism.[30]

The Convention of Ackerman in 1826, the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829 and finally, the Hatt-i Sharif of 1830, recognized the suzerainty of Serbia with Miloš Obrenović I as its hereditary Prince.[31][32] The struggle for liberty, a more modern society and a nation-state in Serbia won a victory under first constitution in the Balkans on 15 February 1835. It was replaced by a more conservative Constitution in 1838. In the two following decades, temporarily ruled by the Karadjordjevic dynasty, the Principality actively supported the neighboring Habsburg Serbs, especially during the 1848 revolutions. Interior minister Ilija Garašanin published The Draft (for South Slavic unification), which became the standpoint of Serbian foreign policy from the mid-19th century onwards. The government thus developed close ties with the Illyrian movement in Croatia-Slavonia region that was a part of the Austria-Hungary.

Following the clashes between the Ottoman army and civilians in Belgrade in 1862, and under pressure from the Great Powers, by 1867 the last Turkish soldiers left the Principality. By enacting a new constitution without consulting the Porte, Serbian diplomats confirmed the de facto independence of the country. In 1876, Serbia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, proclaiming its unification with Bosnia. The formal independence of the country was internationally recognized at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, which formally ended the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78; this treaty, however, prohibited Serbia from uniting with Bosnia and Raška region by placing them under Austro-Hungarian occupation.[33]

From 1815 to 1903, Principality of Serbia was ruled by the House of Obrenović, except from 1842 to 1858, when it was led by Prince Aleksandar Karađorđević. In 1882, Serbia, ruled by King Milan, was raised to Kingdom. In 1903, following May Overthrow, the House of Karađorđević, descendants of the revolutionary leader Đorđe Petrović assumed power. Serbia was the only country in the region that was allowed by the Great Powers to be ruled by its own domestic dynasty. During the Balkan Wars lasting from 1912 to 1913, the Kingdom of Serbia tripled its territory by reacquiring part of Macedonia,[34] Kosovo, and parts of Serbia proper. As for Vojvodina, during the 1848 revolution in Austria, Serbs of Vojvodina established an autonomous region known as Serbian Vojvodina. As of 1849, the region was transformed into a new Austrian crown land known as the Serbian Voivodship and Tamiš Banat. Although abolished in 1860, Habsburg emperors claimed the title Großwoiwode der Woiwodschaft Serbien until the end of the monarchy and the creation of Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in 1918.

Balkan wars and World War I

Balkan Wars refer to the two wars that took place in South-eastern Europe in 1912 and 1913. The First Balkan War broke out when the member states of the Balkan League) attacked and divided Ottoman territories in the Balkans, in a seven-month campaign resulting in the Treaty of London. For Kingdom of Serbia this victory enabled territorial expansion into Raška (Sandžak) region and Kosovo. The Second Balkan War soon ensued when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its gains, turned against its former allies, Serbia and Greece. Their armies repulsed the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked penetrating into Bulgaria, while Romania and the Ottomans used the favourable time to intervene against Bulgaria to win territorial gains. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost most of the territories gained in the First Balkan War, and Kingdom of Serbia annexed Vardar Macedonia. Kingdom of Serbia has enlarged its teritorry by 80% and its population by 50% within just two years; it has also suffered high casualties in the eve of World War I, with around 20,000 dead in the Balkan campaigns.[35]

On 28 June 1914 the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria at Sarajevo in Bosnia-Herzegovina by Gavrilo Princip, a Yugoslav nationalist member of Young Bosnia, and an Austrian citizen, led to Austria-Hungary declaring war on Kingdom of Serbia.[36] In defense of its ally Serbia, Russia started to mobilize its troops, which resulted in Austria-Hungary's ally Germany declaring war on Russia. The retaliation by Austria-Hungary against Serbia activated a series of military alliances that set off a chain reaction of war declarations across the continent, leading to the outbreak of World War I within a month.[37]

The Serbian Army won several major victories against Austria-Hungary at the beginning of World War I, such as the Battle of Cer and Battle of Kolubara – marking the first Allied victories against the Central Powers in World War I.[38] Despite initial success it was eventually overpowered by the joint forces of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria in 1915. Most of its army and some people went into exile to Greece and Corfu where they recovered, regrouped and returned to the Macedonian front during the World War I to lead a final breakthrough through enemy lines on 15 September 1918, freeing Serbia again and defeating Austro-Hungarian Empire and Bulgaria.[39] Serbia, with its campaign was a major Balkan Entente Power[40] which contributed significantly to the Allied victory in the Balkans in November 1918, especially by enforcing Bulgaria's capitulation with the aid of France.[41] The country was militarilly classified as a minor Entente power.[42] Serbia was also among the main contributors to the capitulation of Austria-Hungary in Central Europe.

Serbia's casualties accounted for 8% of the total Entente military deaths or 58% of the regular Serbian Army (420,000 strong) has perished during the conflict.[43] The total number of casualties is placed around 1,000,000[44]-> 25% of Serbia's prewar size, and an absolute majority (57%) of its overall male population.[45] L.A. Times and N.Y. Times also cited over 1,000,000 victims in their respective articles.[46][47]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

- Syrmia region was the first among former Habsburg lands to declare union with the Kingdom of Serbia on 24 November 1918.

- Banat, Bačka and Baranja – together called Vojvodina – joined the Kingdom on the next day.

- On 26 November 1918, the Podgorica Assembly deposes the House of Petrovic-Njegos of the Kingdom of Montenegro, opting for the Karadjordjevic dynasty (the ruling dynasty of the Kingdom of Serbia), de facto unifying the two states.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina declares its unification with Belgrade

- On 1 December 1918, the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and the Kingdom of Serbia joined the unitary Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, that later evolved into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. King Peter I of Serbia became King Peter I of Yugoslavia.

World War II and civil war in Serbia

In 1941, in spite of domestically unpopular attempts by the government of Yugoslavia to appease the Axis powers, Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and other Axis states invaded Yugoslavia. After the invasion, the Kingdom of Yugoslavia was dissolved and Serbia was put under a German Military administration, under a joint German-Serb government with Milan Nedić as Head of the "Government of National Salvation". Serbia was the scene of a civil war between Royalist Chetniks commanded by Draža Mihailović and Communist Partisans commanded by Josip Broz Tito. Against these forces were arrayed Nedić's units of the Serbian Volunteer Corps and the Serbian State Guard.

After one year of occupation, around 16,000 Serbian Jews were murdered in Axis-occupied Serbia, or around 90% of its pre-war Jewish population. Banjica concentration camp was established by the German Military Administration in Serbia.[48] Primary victims were Serbian Jews, Roma, and Serb political prisoners.[49] Other camps in Serbia included the Crveni Krst concentration camp in Niš and the Dulag 183 in Šabac. Staro Sajmište was one of the first concentration camps for Jews in Europe. Staro Sajmište was the largest concentration camp in Axis-occupied Serbia.[50]

Relations between Serbs and Croats in Yugoslavia severely deteriorated during World War II as a result of the creation of the Axis puppet state of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) that comprised most of present-day Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and parts of present-day Serbia's Autonomous Province of Vojvodina. The NDH committed large scale persecution and genocide of Serbs, Jews, and Roma.[51] The number of Serbs and others killed varies in sources, but all agree that hundreds of thousands of people were killed. The (lower) estimate by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum say that NDH authorities murdered between 330,000 and 390,000 ethnic Serb residents of Croatia, Bosnia and parts of Serbia[52] during the period of Ustaše genocide campaign;[53] same figures are supported by the Jewish Virtual Library.[54] The Yad Vashem center reports that over 500,000 Serbs were killed overall in the NDH,[55] whereas the official Yugoslav sources used to estimate over 700,000 victims, mostly Serbs (controversial). The Jasenovac memorial so far lists 75,159 names killed in this concentration camp alone,[56] out of around 100,000 estimated victims.[57] In April 2003 Croatian president Stjepan Mesić apologized on behalf of Croatia to the victims of Jasenovac.[58] In 2006, on the same occasion, he added that to every visitor to Jasenovac it must be clear that Holocaust, genocide and war crimes took place there.[59]

Out of about 1 million casualties in entire Yugoslavia until 1944,[60][61] around 250,000 were Serbia nationals of different ethnicities.[62] The overall number of ethnic Serb casualties in Yugoslavia was around 530,000, out of whom up to 400,000 in the NDH genocide campaign.[63] By late 1944, the joint Soviet and Bulgarian invasion swung in favour of the partisans in the civil war; communists were subsequently established as the ruling elite, whereas the Karadjordjevic dynasty was banned from returning to Serbia.[64] The Syrmia front was the last sequence of the internal war in Serbia following the Soviet-led Belgrade Offensive. Around 70,000 people in Serbia alone perished as the consequence of communist takeover (1944–1946),[65] (around 10,000 of whom were Belgraders)[66] whereas Ministry of Justice figures puts lower estimate around 80,000, of whom 60,000 were of Serbian origin.[67][68]

Serbia within Socialist Yugoslavia

The communist takeover resulted in abolition of the Kingdom, ban on the royal family's return and a subsequent orchestrated constitutional referendum on the republic-socialist type of government.[69] In the aftermath of the victory of the communist Yugoslav Partisans, a totalitarian single-party state was soon established in Yugoslavia by the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. All opposition was repressed and people deemed to be promoting opposition to the government or promoting separatism were given harsh prison sentences or executed for sedition. Serbia became a constituent republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia known as the Socialist Republic of Serbia and had a republic-branch of the federal Communist party, the League of Communists of Serbia. The republic consisted of Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, Socialist Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, and Central Serbia.

One of Serbia's most powerful and influential politicians in this period was Aleksandar Ranković, a high-ranking official in the federal Communist party who was considered one of the "big four" Yugoslav Communists, alongside Josip Broz Tito, Edvard Kardelj, and Milovan Đilas and who was popular in Serbia.[70] Ranković served as head of the UDBA internal security organization and served as vice-president of Yugoslavia from 1963 to 1966.[70] In 1950, Ranković as minister of interior reported that since 1945 the Yugoslav communist regime had arrested five million people.[71] For years Ranković served as Tito's right-hand man and supported Tito's decision to break Yugoslavia away from domination by Soviet Union by having the UDBA obstruct the USSR's efforts to infiltrate state infrastructure and the Yugoslav Communist party.[72] These actions resulted in the USSR-led Cominform accusing the Yugoslav government of being dominated by a "Tito-Ranković clique" that they accused of being a fascist regime.[73] He supported a centralized Yugoslavia and opposed efforts that promoted decentralization that he deemed to be against the interests of Serb unity.[70] Ranković sought to secure the position of the Serbs in Kosovo and gave them dominance in Kosovo's nomenklatura.[70] Ranković's power and agenda waned in the 1960s with the rise to power of reformers who sought decentralization and to preserve the right of national self-determination of the peoples of Yugoslavia.[74] In response to his opposition to decentralization, the Yugoslav government removed Ranković from office in 1966 on various claims, including that he was spying on Tito.[74] Ranković's dismissal was highly unpopular amongst Serbs.[74]

After the ouster of Ranković, the agenda of pro-decentralization reformers in Yugoslavia, especially from Slovenia and Croatia succeeded in the late 1960s in attaining substantial decentralization of powers, creating substantial autonomy in Kosovo and Vojvodina, and recognizing a Muslim Yugoslav nationality.[74] As a result of these reforms, there was a massive overhaul of Kosovo's nomenklatura and police, that shifted from being Serb-dominated to ethnic Albanian-dominated through firing Serbs in large scale.[74] Further concessions were made to the ethnic Albanians of Kosovo in response to unrest, including the creation of the University of Pristina as an Albanian language institution.[74] These changes created widespread fear amongst Serbs that they were being made second-class citizens in Yugoslavia by these changes.[75] These changes was harshly criticized by Serbian communist official Dobrica Ćosić, who at the time claimed that they were contrary to Yugoslavia's commitment to Marxism through conceding to nationalism, especially Albanian nationalism.[76]

Dissolution of Yugoslavia

Slobodan Milošević rose to power in Serbia in 1989 in the League of Communists of Serbia through a series of coups against incumbent governing members. Milošević promised reduction of powers for the autonomous provinces of Kosovo and Vojvodina. This ignited tensions with the communist leadership of the other republics that eventually resulted in the secession of Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia from Yugoslavia.[77]

Multiparty democracy was introduced in Serbia in 1990, officially dismantling the former one-party communist system. Critics of the Milošević government claimed that the Serbian government continued to be authoritarian despite constitutional changes as Milošević maintained strong personal influence over Serbia's state media.[78][79] Milošević issued media blackouts of independent media stations' coverage of protests against his government and restricted freedom of speech through reforms to the Serbian Penal Code which issued criminal sentences on anyone who "ridiculed" the government and its leaders, resulting in many people being arrested who opposed Milošević and his government.[80]

The period of political turmoil and conflict marked a rise in ethnic tensions and between Serbs and other ethnicities of the former Communist Yugoslavia as territorial claims of the different ethnic factions often crossed into each others' claimed territories. Serbs feared that the nationalist and separatist government of Croatia was led by Ustase sympathizers who would oppress Serbs living in Croatia while also accused was the separatist government of Bosnia and Herzegovina, being led by Islamic fundamentalists. The governments of Croatia and Bosnia in turn accused the Serbian government of attempting to create a Greater Serbia. These views led to a heightening of xenophobia between the peoples during the wars.

In 1992, the governments of Serbia and Montenegro agreed to the creation of a new Yugoslav federation called the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia which abandoned the predecessor SFRY's official endorsement of communism, and instead endorsed democracy. In response to accusations that the Yugoslav government was financially and militarily supporting the Serb military forces in Bosnia & Herzegovina and Croatia, sanctions were imposed by the United Nations, during the 1990s, which led to political isolation, economic decline and hardship, and serious hyperinflation of currency in Yugoslavia.

Milošević represented the Bosnian Serbs at the Dayton peace agreement in 1995, signing the agreement which ended the Bosnian War that internally partitioned Bosnia & Herzegovina largely along ethnic lines into a Serb republic and a Bosniak-Croat federation.

When the ruling Socialist Party of Serbia refused to accept municipal election results in 1997, which resulted in its defeat in the municipalities, Serbians engaged in large protests against the Serbian government and government forces held back the protesters.

Between 1998 and 1999, peace was broken when the worsened situation in Kosovo with continued clashes in Kosovo between the Yugoslav security forces and Kosovo Liberation Army, locally known as the Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës, or the KLA. The confrontations led to a multi-nation conflict called the Kosovo War.

Political transition

In September 2000, opposition parties claimed that Milošević committed fraud in routine federal elections. Street protests and rallies throughout Serbia eventually forced Milošević to concede and hand over power to the recently formed Democratic Opposition of Serbia (Demokratska opozicija Srbije, or DOS). The DOS was a broad coalition of anti-Milošević parties. On 5 October, the fall of Milošević led to end of the international isolation Serbia suffered during the Milošević years. Milošević was sent to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia on accusations of sponsoring war crimes and crimes against humanity during the wars in Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo which he was held on trial to until his death in 2006. With the fall of Milošević, Serbia's new leaders announced that Serbia would seek to join the European Union. In October 2005, the EU opened negotiations with Serbia for a Stabilization and Association Agreement, a preliminary step towards joining the EU.

Serbia's political climate since the fall of Milošević remained tense. In 2003, the prime minister Zoran Đinđić was assassinated as result of a plot originating from circles of organized crime and former security forces. Nationalist and EU-oriented political forces in Serbia have remained sharply divided on the political course of Serbia in regards to its relations with the European Union and the West. However, the tensions between those political poles gradually eased since, as the issues of Kosovo independence, economical crisis and aspiration towards accession to the European Union forced the parties to find more common ground.

From 2003 to 2006, Serbia was part of the "State Union of Serbia and Montenegro." This union was the successor to the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On 21 May 2006, Montenegro held a referendum to determine whether or not to end its union with Serbia. The next day, state-certified results showed 55.4% of voters in favor of independence. This was just above the 55% required by the referendum.[81]

Independent Serbia

On 5 June 2006, following the referendum in Montenegro, the National Assembly of Serbia declared the "Republic of Serbia" to be the legal successor to the "State Union of Serbia and Montenegro."[82] Serbia and Montenegro became separate nations. However, the possibility of a dual citizenship for the Serbs of Montenegro is a matter of the ongoing negotiations between the two governments. In April 2008 Serbia was invited to join the intensified dialogue programme with NATO despite the diplomatic rift with the Alliance over Kosovo.[83]

Serbia officially applied for the EU membership on 22 December 2009.[84] The government of Serbia has the goal for the EU accession in 2014 per the Papandreou plan - Agenda 2014.[85][86] European Commission's Vice President Jacques Barrot seems to back this initiative, predicting Serbia's EU accession within 5 to 7 years following its formal application.[87]

Geography

Located at the crossroads between Central and Southern Europe Serbia is found in the Balkan peninsula and the Pannonian Plain. The Danube passes through Serbia with 21% of its overall length, joined by its biggest tributaries, the Sava and Tisza rivers.[88] The province of Vojvodina covers the northern third of the country, and is entirely located within the Central European Pannonian Plain. Dinaric mountains, gradually rising towards south, cover most of western and central Serbia. The easternmost tip of Serbia extends into the Wallachian Plain. The eastern border of the country intersects with the Carpathian Mountain range,[89] which run through the whole of Central Europe.

The Southern Carpathians meet the Balkan Mountains, following the course of the Great Morava, a 500 km long river. The Midžor peak is the highest point in eastern Serbia at 2156 m. In the southeast, the Balkan Mountains meet the Rhodope Mountains. The Šar Mountains of Kosovo form the border with Albania, with one of the highest peaks in the region, Djeravica, reaching 2656 meters at its peak. Dinaric Alps of Serbia follow the flow of the Drina river, overlooking the Dinaric peaks on the opposite shore in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

National parks

Over 31% of Serbia is covered by forest.[90] National parks take up 10% of the country's entire territory.[91]

| Name | Established | Size in hectares | Map | Picture |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National park Djerdap | 1974 | 93.968 |

|

|

| National Park Kopaonik | 1981 | 11.810 |

|

|

| National Park Tara | 1981 | 22.000 |

|

|

| National Park Šarplanina | 1986 | 39.000 |

|

|

| National Park Fruska Gora | 1960 | 25.393 |

|

|

Wetlands

| Name | Designated | Municipality | Area (km²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gornje Podunavlje | 2007 | Vojvodina | 224,8 |

| Labudovo okno | 2006 | Bela Crkva | 37,33 |

| Ludaš Lake | 1977 | Subotica | 5,93 |

| Obedska bara | 1977 | Pećinci | 175,01 |

| Peštersko polje | 2006 | Sjenica | 34,55 |

| Slano Kopovo | 2004 | Vojvodina | 9,76 |

| Stari Begej - Carska Bara | 1996 | Zrenjanin | 17,67 |

| Vlasina Lake | 2007 | Surdulica | 32,09 |

Climate

The Serbian climate varies between a continental climate in the north, with cold winters, and hot, humid summers with well distributed rainfall patterns, and a more Adriatic climate in the south with hot, dry summers and autumns and relatively cold winters with heavy inland snowfall. Differences in elevation, proximity to the Adriatic Sea and large river basins, as well as exposure to the winds account for climate differences.[92] Vojvodina possesses typical continental climate, with air masses from northern and western Europe which shape its climatic profile. South and South-west Serbia is subject to Mediterranean influences. However, the Dinaric Alps and other mountain ranges contribute to the cooling down of most of the warm air masses. Winters are quite harsh in Sandžak because of the mountains which encircle the plateau.[93]

Mediterranean micro-regions exist throughout southern Serbia,[94] in Zlatibor[95] and the Pčinja District around valley and river Pčinja.[96] The average annual air temperature for the period 1961–90 for the area with an altitude of up to 300 m (984 ft) is 10.9 °C (51.6 °F). The areas with an altitude of 300 to 500 m (984 to 1,640 ft) have an average annual temperature of around 10.0 °C (50.0 °F), and over 1,000 m (3,281 ft) of altitude around 6.0 °C (42.8 °F).[97] The lowest recorded temperature in Serbia was −39.5 °C (−39.1 °F) in January 13, 1985, Karajukića Bunari in Pešter, and the highest was 44.9 °C or 112.8 °F, in July 24, 2007, recorded in Smederevska Palanka.[97] On July 23, 2007, temperatures were as high as 46 °C or 114.8 °F.

Environment

Serbia's environment is monitored by the Ministry for Science and Environmental Protection. a federally funded governmental agency called SEPA, or Serbian Environmental Protection Agency,is responsible for environmental cleanups and protection of wildlife in Serbia.[98] The NATO bombings of 1999 caused lasting damage to the environment of Serbia, with several thousand tons of toxic chemicals stored in targeted factories being released into the soil, atmosphere, and water basins affecting humans and the local wildlife.[99] Recycling is still a fledgeling activity in Serbia, with only 15% of its waste being turned back for re-use, while the Ministry for Science and Environmental Protection is moving towards improving the situation.[100]

The Serbian Energy Efficiency Agency, SEEA, was founded in May 2002. A national non-profit organization, it develops and proposes programmes and measures, co-ordinates and stimulates activities intended to achieve rational use and saving of energy, as well as the increase in efficiency of energy use in all sectors of consumption.[101] The country is looking towards making wider use of renewable energy, a 20 megawatt wind farm is being developed in Belo Blato as part of a 300 megawatt development plan.[102]

Water

Spanning over 588 kilometers across Serbia, the Danube river is the largest source of fresh water. Other freshwater rivers are Sava, Morava, Tisza, and Timok. Almost all of Serbia's rivers drain to the Black Sea, by way of the Danube river. One notable exception is the Pčinja which flows into the Aegean. The largest natural lake is Belo Jezero, located in Vojvodina, covering 25 square kilometers. The largest artificial reservoir, Đerdap, locally known as Đerdapsko Lake, covers an area of 163 square kilometers on the Serbian side, and it has a total area of 253 square kilometers. The largest waterfall, Jelovarnik, located in Kopaonik, is 71 meters high.

| River | Km in Serbia | Total length (km) |

Number of countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Danube | 588 | 2783 | 9 |

| 2 | Great Morava | 493 | 493 | 1 |

| 3 | Ibar | 250 | 272 | 2 |

| 4 | Drina | 220 | 346 | 3 |

| 5 | Sava | 206 | 945 | 4 |

| 6 | Timok | 202 | 202 | 1 |

| 7 | Tisa | 168 | 966 | 4 |

| 8 | Nišava | 151 | 218 | 2 |

| 9 | Tamiš | 118 | 359 | 2 |

| 10 | Begej | 75 | 244 | 2 |

Government

After the formation of the Republic of Serbia in 2006, the government quickly proclaimed a referendum that ousted the old Milošević-era constitution and created the new framework for the newly created nation by ratifying a new Constitution of Serbia. Serving his second term President Boris Tadić is the leader of the center-left Democratic Party. His second reelection was won with a narrow 50.5% majority in the second round of the presidential election held on 4 February 2008.

Parliamentary elections were held in May 2008. The coalition For a European Serbia led by President Tadics' party claimed victory, but was significantly short of an absolute majority. Following the negotiations with the leftist coalition centered around the Socialist Party and parties of national minorities, those of Hungarians, Bosniaks and Albanians, an agreement was reached to make-up a new government, headed by Mirko Cvetković. Present-day Serbian politics are fractiously divided on different issues, such as Serbia's role in the European Union and the scale of government intervention in the economy.

Kosovo has been governed since 1999 by UNMIK, a UN mission. The current Special Representative, Lamberto Zannier, oversees the governance of Kosovo. The Provisional Institutions of Self-Government, has an assembly and a president, currently Fatmir Sejdiu. Although the assembly has declared independence from Serbia, the legality of this move is unclear and is currently being debated in the International Court of Law.

Foreign relations

The Foreign Minister, currently Vuk Jeremić, serves as a director responsible for the Serbian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a government organization that seeks to maintain and improve neighborly relations among other goals. The four goals for the minister in 2010 are to maintain Serbia's territorial integrity, aid the accession of Serbia to the European Union, develop good neighborly relations and aid economic diplomacy.[103]

Administrative divisions

The territorial organization of Serbia is regulated by the Law on Territorial Organization,[104] adopted in the National Assembly of Serbia on 29 December 2007.[106] Under the Law, the units of the territorial organization are: municipalities, cities and autonomous provinces.[104]

Serbia is divided into 150 municipalities and 24 cities, which are the basic units of local self-government.[104] The city may or may not be divided into "city municipalities" (gradske opštine). Five cities, Belgrade, Novi Sad, Niš, Kragujevac and Požarevac comprise several municipalities, divided into "urban" (in the city proper) and "other" (suburban). There are 31 city municipalities (17 in Belgrade, 5 in Niš, 5 in Kragujevac, 2 in Novi Sad and 2 in Požarevac). Of the 150 municipalities, 83 are located in Central Serbia, 39 in Vojvodina and 28 in Kosovo. Of the 24 cities, 17 are in Central Serbia, 6 are in Vojvodina and 1 in Kosovo.[104]

Serbia has two autonomous provinces: Vojvodina in the north (which includes 39 municipalities and 6 cities) and Kosovo and Metohija[104] in the south (with 28 municipalities and 1 city). The Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija has been transferred to the UN administration of UNMIK since June 1999. In February 2008, the Government of Kosovo declared its independence, a move recognized by a minority of countries (most of the European Union and USA) but not recognized by Serbia or the United nations. Autonomous province has its own assembly and executive council (government). It enjoys autonomy on the certain meters like education and culture. The area that lies between Vojvodina and Kosovo is called Central Serbia. Central Serbia is not an administrative division (unlike the autonomous provinces), and it has no regional government of its own.

Municipalities and cities are gathered into districts, which are regional centers of state authority, but have no assemblies of their own; they present purely administrative divisions, and host various state institutions such as funds, office branches and courts. Districts are not defined by the Law on Territorial Organisation, but are organised under the Government's Enactment of 29 January 1992.[105] Serbia is divided into 29 districts (17 in Central Serbia, 7 in Vojvodina and 5 in Kosovo), while the city of Belgrade presents a district of its own.

Defense

Serbia is a constitutionally declared neutral country, as such it is not a member of a military alliance, nor does it participate in foreign combat operations. It does however participate in peacekeeping operations under United Nations authority.[11]

Conscription is still mandatory with regular service lasting 6 months, but a high number of recruits take the opportunity to put forth conscientious objection and serve 9 months in civil service.[107] Thorough reforms and full professionalization are underway. Currently, the largest portion of the budget goes to paying pensions and salaries of soldiers. Professionalization of the military is expected to be completed by the end of 2010.[108]

Demographics

.png)

As of January 2010, Serbia without Kosovo is estimated to have 7,334,935 citizens (not including over 200,000 internally displaced persons from Kosovo, who will be counted as a permanent population in next census, taking place in 2011).[109] The 2002 census was not conducted in Kosovo, which was under United Nations administration at the time. According to CIA estimates, Kosovo has around 1,8 million inhabitants, majority of them Albanian with Serbs of Kosovo coming in second place.[110]

Ethnic Serbs, or those who identify have declared themselves only as Serbs, are the largest ethnic group in Serbia and they represent 83% of the total population. With a population of 290.000, Hungarians are the second largest ethnic group in Serbia, representing 3.9% (and 14.3% of the population in Vojvodina). Other minority groups include Bosniaks, Roma, Albanians, Croats, Bulgarians, Montenegrins, Slovaks, Vlachs and Romanians.[111]

Refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Serbia form between 7% and 7.5% of its population – about half a million refugees sought refuge in the country following the series of Yugoslav wars, mainly from Croatia, and to a lesser extent from Bosnia and Herzegovina and the IDPs from Kosovo, which are currently the most numerous at over 200,000.[112] Serbia has the largest refugee population in Europe.[113]

On the other hand, it is estimated that 300,000 people have left Serbia during the '90s alone, and around 20% of those had college or higher education.[114][115] Serbia has comparatively very old overall population (among the top 10 oldest in the world), mostly due to low level of fertility. In addition, Serbia has among the highest negative growth population rates in the world, ranking 225th out of 233 countries overall.[116]

Largest cities

| Leading urban areas of Serbia (excluding Kosovo)[117] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Core city | Urban population[118] | Municipal population[118] |

|

||||||

| 1 | Belgrade | 1,119,642[119] | 1,576,124 | |||||||

| 2 | Novi Sad | 191,405 | 299,294 | |||||||

| 3 | Niš | 173,724 | 250,518 | |||||||

| 4 | Kragujevac | 146,373 | 175,802 | |||||||

| 5 | Subotica | 99,981 | 148,401 | |||||||

| 6 | Zrenjanin | 79,773 | 132,051 | |||||||

| 7 | Pančevo | 77,087 | 127,162 | |||||||

| 8 | Čačak | 73,217 | 117,072 | |||||||

| 9 | Leskovac | 63,185 | 156,252 | |||||||

| 10 | Smederevo | 62,805 | 109,809 | |||||||

| 11 | Valjevo | 61,035 | 96,761 | |||||||

| 12 | Kraljevo | 57,411 | 121,707 | |||||||

| 13 | Kruševac | 57,347 | 131,368 | |||||||

| 14 | Šabac | 55,163 | 122,893 | |||||||

| 15 | Vranje | 55,052 | 87,288 | |||||||

| 16 | Užice | 54,717 | 83,022 | |||||||

| 17 | Novi Pazar | 54,604 | 85,996 | |||||||

| 18 | Sombor | 51,471 | 97,263 | |||||||

| 19 | Kikinda | 41,935 | 67,002 | |||||||

| 20 | Požarevac | 41,736 | 74,902 | |||||||

Religion

For centuries straddling the religious boundary between Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism, joined up later by Islam, Serbia remains one of the most diverse countries on the continent. While formation of the nation-state and turbulent history of 19th and 20th century has left its traces on the religious landscape of the country: Vojvodina is still 25% Catholic or Protestant, while Central Serbia and Belgrade regions are over 90% Orthodox Christian.[111] Kosovo consists of a 90% Albanian Muslim majority.

Among the Eastern Orthodox churches, the Serbian Orthodox Church is the largest. According to the 2002 Census,[120] 82% of the population of Serbia, excluding Kosovo, or 6,2 million people declared their nationality as Serbian, who are overwhelmingly adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Other Orthodox Christian communities in Serbia include Montenegrins, Romanians, Vlachs, Macedonians and Bulgarians. Together they comprise about 84% of the entire population.

Catholicism is mostly present in Vojvodina, especially its northern part, which is home to minority ethnic groups such as Hungarians, Slovaks, Croats, Bunjevci, and Czechs. There are an estimated 388,000 baptized Catholics in Serbia, roughly 6.2% of the population, mostly in northern Serbia.[111]

Protestantism accounts for about 1.1% of the country's population, chiefly among Reformist Hungarians and Slovaks in Vojvodina. Islam has a strong historic following in the southern regions of Serbia – Sandžak (Raška) region and Preševo, Bujanovac and Medveđa municipalities in the south-east. Bosniaks are the largest Muslim community in Serbia with 140,000 followers or 2% of the total population, followed by Albanians,[111] whereas a part of Serbian Roma are Muslim.

With the exile of Jews from Spain during the Inquisition era, thousands of escaping families and individuals made their way through Europe to the Balkans. A goodly number settled in Serbia and became part of the general population. They were well-accepted and during the ensuing generations the majority assimilated or became traditional or secular, rather than remain orthodox as had been the original immigrants. Later on the wars that ravaged the region resulted in a great part of the Serbian Jewish population emigrating from Europe.

Economy

With a GDP PPP for 2010 estimated at $80.602 billion[2] or $10,897 per capita PPP, the Republic of Serbia is an upper-middle income economy by the World Bank.[121] Foreign Direct Investment in 2006 was $5.85 billion or €4.5 billion. FDI for 2007 reached $4.2 Billion while real GDP per capita figures are estimated to have reached $6,781 in April 2009.[2] The GDP growth rate showed increase by 6.3% in 2005,[122] 5.8% in 2006,[123] reaching 7.5% in 2007 and 8.7% in 2008[124] as the fastest growing economy in the region.[125] According to Eurostat data, Serbian PPS GDP per capita stood at 37 per cent of the EU average in 2008.[126]

.jpg)

The economy has a high unemployment rate of 14%[127] and a unfavourable trade deficit. The country expects some major economic impulses and high growth rates in the next years. Given its recent high economic growth rates, which averaged 6.6% in the last three years, foreign analysts have sometimes labeled Serbia as the "Balkan Tiger".

Apart from its free-trade agreement with the EU as its associate member, Serbia is the only European country outside the former Soviet Union to have free trade agreements with the Russian Federation and, more recently, Belarus.[128] Apart from its favorable economic agreements with both the East and West, such steps could be soon undertaken with Turkey and Iran.[129] By doing this Serbia hopes to set up an export-oriented economy.[129]

Blue-chip corporations investing in Serbia include: US Steel, Philip Morris, Microsoft, FIAT, Coca-Cola, Lafarge, Siemens, Carlsberg and others.[130][131] In the energy, Russian giants Lukoil and Gazprom have invested heavily.[132] The banking sector has attracted investments from Banca Intesa Italy, Crédit Agricole and Société Générale France, HVB Bank Germany, Erste Bank Austria, Eurobank EFG and Piraeus Bank Greece, and others.[133] U.S. based Citibank, opened a representative office in Belgrade in December 2006.[134] In the trade sector, biggest foreign investors are France's Intermarche, German Metro Cash & Carry, Greek Veropoulos, and Slovenian Mercator.

Serbia grows about one-third of the world's raspberries and is the leading frozen fruit exporter.[135]

Communication

89% of households in Serbia have fixed telephone lines, and with over 9.60 million users the number of cell-phones surpasses the number of total population population of Serbia itself by 30%. Largest cellphone providers are Telekom Srbija with 5.65 million subscribers, Telenor with 3.1 million users and Vip mobile covering the rest of the population.[136] 46.8% of households have computers, 36.7% use the internet, and 42% have cable TV, which puts the country ahead of certain member states of the EU.[137][138][139][140] Serbia is ranked 59th in the world in terms of Internet usage out of 216 states by the CIA World Factbook.[141] With 45% of its population using the internet, Serbia is ahead of all Balkan countries except for Croatia in terms of internet service penetration.[142]

Transportation

Serbia owns one of the world's oldest airline carriers, Jat Airways, founded in 1927.[143] There are 4 international airports in Serbia: Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport, Niš Constantine the Great Airport and Vršac international airport as well as one in Kosovo, Pristina International Airport .

Historians have labeled the entire Serbia, and especially the valley of the Morava, as "the crossroads between East and West", which is one of the primary reasons for its turbulent history. The Morava valley route, which avoids mountainous regions, is by far the easiest way of traveling overland from continental Europe to Greece and Asia Minor. Modern Serbia was the first among its neighbors to buy railroads- in 1858 the first train arrived to Vrsac, then Austria-Hungary[144] (by 1882 route to Belgrade and Niš was completed). Serbian Railways handles the entire railway links in Serbia.

European routes E65, E70, E75 and E80, as well as the E662, E761, E762, E763, E771, and E851 pass through the country. The E70 westwards from Belgrade and most of the E75 are modern highways of motorway / autobahn standard or close to that. As of 2005, Serbia has 1,481,498 registered cars, 16,042 motorcycles, 9,626 buses, 116,440 trucks, 28,222 special transport vehicles, 126,816 tractors, and 101,465 trailers.[145]

Water transportation

Although landlocked, there are around 2000 km of navigable rivers and canals, the largest of which are: the Danube, Sava, Tisa, joined by the Timiş River and Begej, all of which connect Serbia with Northern and Western Europe through the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal and North Sea route, to Eastern Europe via the Tisa, Timiş, Begej and Danube Black Sea routes, and to Southern Europe via the Sava river. The two largest Serbian cities – Belgrade[146] and Novi Sad, as well as Smederevo – are major regional Danubian harbours.[147] The Danube River, central Europe's connection to the Black Sea, flows through Serbia. Through Danube-Rhine-Main canal the North Sea is also accessible. Tisza river offers a connection with Eastern Europe while the Sava river connects her to western former Yugoslav republics near the Adriatic Sea.

Tourism

Serbia's government, businesses, and citizen's concentrate their tourism on the villages and mountains of the country. The most famous mountain resorts are Zlatibor, Kopaonik, and the Tara. There are also many spas in Serbia, one the biggest of which is Vrnjačka Banja. Other spas include Soko Banja and Niška Banja. There is a significant amount of tourism in the largest cities like Belgrade, Novi Sad and Niš, but also in the rural parts of Serbia like the volcanic wonder of Đavolja varoš,[148] Christian pilgrimage across the country[149] and the cruises along the Danube, Sava or Tisza. There are several popular festivals held in Serbia, such as the EXIT Festival, proclaimed to be the best European festival by UK Festival Awards 2007 and Yourope, the European Association of the 40 largest festivals in Europe and the Guča trumpet festival. 2,2 million tourists visited Serbia in 2007, a 15% increase compared to 2006.[150]

Energy

Most of the energy is currently produced comes from coal or hydroelectric dams. Energy consumption is expected to exceed energy production by 2012 and Elektroprivreda Srbije, Serbia's largest energy producer, is expected to develop Đerdap III (Ђердап III), a hydroelectric dam with approximately 2.4 gigawatts of power.[151]

Naftna Industrija Srbije (Нафтна Индустрија Србије / Naftna industrija Srbije), Serbia's largest oil producer was recently acquired by Russian energy giant Gazprom. The two companies, are planning to build the Serbian portion of the South Stream gas pipeline. The two companies are also building a 300 million cubic meters gas storage at Banatski Dvor, located approximately 60 kilometers northeast of Novi Sad. overall, the South Stream gas pipeline project will be the largest since the 19th century railway construction through Serbia.

Culture

For centuries straddling the boundaries between East and West, Serbia had been divided among: the Eastern and Western halves of the Roman Empire; between Kingdom of Hungary, Bulgarian Empire, Frankish Kingdom and Byzantium; and between the Ottoman Empire and the Austrian Empire and Austria-Hungary, as well as Venice in the south. The result of these overlapping influences are distinct characters and sharp contrasts between various Serbian regions, its north being more tied to Western Europe and south leaning towards the Balkans and the Mediterranean Sea.

The Byzantine Empire's influence on Serbia was profound, through introduction of Greek Orthodoxy from 7th century onwards today Serbian Orthodox Church has an overwhelming influence on the makeup of cultural objects in Serbia. Different influences were also present- chiefly the Ottoman, Hungarian, Austrian and also Venetian, also known as coastal Serbs. Serbs use both the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets.

The monasteries of Serbia, built largely in the Middle Ages, are one of the most valuable and visible traces of medieval Serbia's association with the Byzantium and the Orthodox World, but also with the Romanic Western Europe that Serbia had close ties with back in Middle Ages. Most of Serbia's queens still remembered today in Serbian history were of foreign origin, including Hélène d'Anjou, a cousin of Charles I of Sicily, Anna Dondolo, daughter of the Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, Catherine of Hungary, and Symonide of Byzantium.

Serbia has eight cultural sites marked on the UNESCO World Heritage list: Stari Ras and Sopoćani monasteries added to the Heritage list in 1979, Studenica Monastery added in 1986, the Medieval Serbian Monastic Complex in Kosovo, comprising: Dečani Monastery, Our Lady of Ljeviš, Gračanica and Patriarchate of Pec, monestaties were added in 2004, and put on the endangered list in 2006, and Gamzigrad – Romuliana, Palace of Galerius, was added in 2007. Likewise, there are 2 literary memorials added on the UNESCO's list as a part of the Memory of the World Programme: Miroslav Gospels, handwriting from the 12th century, added in 2005, and Nikola Tesla's archive added in 2003.

The most prominent museum in Serbia is the National Museum, founded in 1844; it houses a collection of more than 400,000 exhibits, over 5600 paintings and 8400 drawings and prints, and includes many foreign masterpiece collections and the famous Miroslavljevo Jevanđelje. Currently museum is under reconstruction. The museum is situated in Belgrade.

Heritage

| Serbia in the list of World Heritage Sites | |||||

| Image | Name | Location | Notes | Date added | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stari Ras | Novi Pazar | Medieval monuments, added as Stari Ras and Sopoćani | 1979 | Cultural[152] |

|

Studenica monastery | Kraljevo | Serbian Orthodox monastery | 1986 | Cultural[153] |

|

Medieval Monuments in Kosovo | Kosovo | Visoki Dečani, Patriarchate of Peć, Our Lady of Ljeviš, Gračanica monastery. Heritage in danger. | 2006 | Cultural[154] |

|

Gamzigrad | Zaječar | Late period Roman sites. | 2007 | Cultural[155] |

Theatre and cinema

Serbia has a well-established theatrical tradition with many theaters. The Serbian National Theatre was established in 1861 with its building dating from 1868. The company started performing opera from the end of the 19th century and the permanent opera was established in 1947. It established a ballet company. Bitef, Belgrade International Theatre Festival, is one of the oldest theatre festivals in the world. New Theatre Tendencies is the constant subtitle of the Festival. Founded in 1967, Bitef has continually followed and supported the latest theater trends. It has become one of five most important and biggest European festivals. It has become one of the most significant culture institutions of Serbia.

Cinema prospered after World War II. The most notable postwar director was Dušan Makavejev who was internationally recognised for Love Affair: Or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator in 1969 focussing on Yugoslav politics. Makavejev's Montenegro was made in Sweden in 1981. Zoran Radmilović was one of the most notable actors of the postwar period. Serbian cinema continued to make progress despite the turmoil in the 1990s. Emir Kusturica won a Golden Palm for Best Feature Film at the Cannes Film Festival for Underground in 1995. In 1998, Kusturica won a Silver Lion for directing Black Cat, White Cat. As at 2001, there were 167 cinemas in Central Serbia and Vojvodina combined, and over 4 million Serbs went to the cinema in that year. In 2005, San zimske noći A Midwinter Night's Dream directed by Goran Paskaljević caused controversy over its criticism of Serbia's role in the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s.

Education

Education in Serbia is regulated by the Ministry of Education. Education starts in either pre-schools or elementary schools. Children enroll in elementary schools (Serbian: Osnovna škola / Основна школа) at the age of seven, and remain there for eight years. After compulsory education students have the opportunity to either attend a high school for another four years, specialist school, for 2 to 4 years, or to enroll in vocational training, for 2 to 3 years. Following the completion of high school or a specialist school, students have the opportunity to attend university.

In Serbia, some of the largest universities are:

- University of Belgrade

- University of Kragujevac

- University of Niš

- University of Novi Sad

- University of Pristina

- University of Novi Pazar

The University of Belgrade is the oldest and currently the biggest university in Serbia. Established in 1808, it has 31 faculties, and since its inception, has trained an estimated 330,000 graduates. Other universities with a significant number of faculty and alumni are those of Novi Sad (founded 1960), Kragujevac (founded 1976) and Niš (founded 1965).

The roots of the Serbian education system date back to the 11th and 12th centuries when the first Catholic colleges were founded in Titel and Bač, in Vojvodina province. Medieval Serbian education, however, was mostly conducted through the Serbian Orthodox monasteries of Sopoćani, Studenica, and Patriarchate of Peć. Serbian Orthodox education starting from the rise of Raška in 12th century, when Serbs overwhelmingly embraced Orthodoxy rather than Catholicism. The oldest college faculty within current borders of Serbia dates back to 1778; founded in the city of Sombor, then Habsburg Empire, it was known under the name Norma and was the oldest Slavic Teacher's college in Southern Europe.[156]

Holidays

All holidays in Serbia are regulated by the Law of national and other holidays in Republic of Serbia (Закон о државним и другим празницима у Републици Србији, Zakon o državnim i drugim praznicima u Republici Srbiji). The following holidays are observed state-wide:[157]

| Date | Name | Serbian name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 January / 2 January | New Year's Day | Нова Година, Nova Godina | non-working holiday |

| 7 January | Orthodox Christmas | Божић, Božić | non-working holiday |

| 27 January | Saint Sava's Day | Савиндан – Дан Духовности, Savindan – Dan Duhovnosti | working holiday (in memory on the founder of the Serbian Orthodox Church) |

| 15 February | Candlemas – Statehood day | Сретење – Дан државности – Sretenje – Dan državnosti | non-working holiday (in memory on the First Serbian Uprising) |

| 2 April | Orthodox Great Friday | Велики петак – Veliki petak | non-working holiday (date for 2010 only) |

| 3 April | Orthodox Great Saturday | Велика субота – Velika subota | non-working holiday (date for 2010 only) |

| 4 April | Orthodox Easter | Васкрс – Vaskrs | non-working holiday (date for 2010 only) |

| 5 April | Orthodox Easter Monday | Велики понедељак – Veliki ponedeljak | non-working holiday (date for 2010 only) |

| 1 May / 2 May | Labour Day | Дан рада – Dan rada | non-working holiday |

| 9 May | Victory Day | Дан победе – Dan pobede | working holiday |

| 28 June | Saint Vitus Day - Vidovdan | Видовдан – Дан Срба палих за отаџбину, Vidovdan – Dan Srba palih za otadžbinu | working holiday (in memory of the Battle of Kosovo in 1389) |

Also, members of other religions have the right not to work on days of their holidays.

Cuisine

Serbian cuisine is varied, the turbulent historical events influenced the food and people, and each region has its own peculiarities and differences. It is strongly influenced by the Byzantine-Greek, Mediterranean, Oriental and Austro-Hungarian styles. Many of the traditional Serbian foods like ćevapčići, soup, pljeskavica, gibanica, are enjoyed even today.

Medenjaci |

Ćevapčići |

Architecture

Serbia has a diverse history and this diversity is reflected in its architecture. Serbian monasteries are built in the style of Byzantine architecture, similar to the architecture of Russian churches. In northern Serbia Baroque style of architecture is predominant while in the south oriental style is dominant. In the capital city, Belgrade, many buildings are built in the Art Deco architectural style. After the second world war, the capital city, Belgrade, expanded westwards. The new neighborhood called, New Belgrade, was built according to Le Corbusier's urban planning ideology. Many of the buildings of Belgrade is shocked that during the time of Yugoslavia were built in the style of socialist modernism. The current predominating architectural style is Western and consists of glass façades.

Sports

Sports in Serbia revolve mostly around team sports: football, basketball, water polo, volleyball, handball, and, more recently, tennis. The two main football clubs in Serbia are Red Star Belgrade and FK Partizan, both from capital Belgrade. Red Star is the only Serbian and former Yugoslav club that has won a UEFA competition, winning the 1991 European Cup in Bari, Italy. The same year in Tokyo, Japan, the club won the Intercontinental Cup. Partizan is the first club from Serbia to take part in the UEFA Champions League group stages subsequent to the breakup of the Former Yugoslavia. The matches between two rival clubs are known as "Eternal Derby" (Serbian: Вечити дерби, Večiti derbi). Serbia and Italy were host nations at 2005 Men's European Volleyball Championship. The Serbia men's national volleyball team is the direct descendant of Yugoslavia men's national volleyball team. After becoming independent, Serbia won bronze medal at 2007 Men's European Volleyball Championship held in Moscow.

Milorad Čavić and Nađa Higl in swimming, Olivera Jevtić, Dragutin Topić in athletics, Aleksandar Karakašević in table tennis, Jasna Šekarić in shooting are also very popular athletes in Serbia.

Basketball

Serbia is one of the traditional powerhouses of world basketball, winning various FIBA World Championships, multiple Eurobaskets and Olympic medals (albeit as FR Yugoslavia). Serbia's national basketball team is considered the successor to the successful Yugoslavia national basketball team. Serbia has won FIBA world championships five times and has won second place in the European championship in 2009. Players from Serbia made deep footprint in history of basketball, having success both in the top leagues of Europe and in the NBA. Many Serbs have played in the NBA such as Vlade Divac, Predrag Stojakovic, Nenad Krstic, Darko Milicic, and Vladimir Radmanovic.

Basketball League of Serbia Is the highest professional basketball to Serbia. For the eighth consecutive year, KK Partizan is currently the reigning champion of the league, followed by KK Crvena Zvezda. KK Partizan was the European champion in 1992 with curiosity of winning the title, although playing all but one of the games (crucial quarter-final game vs. Knorr) on foreign grounds; FIBA decided not to allow teams from Former Yugoslavia play their home games at their home venues, because of open hostilities in the region. KK Partizan was not allowed to defend the title in the 1992–1993 season, because of UN sanction.

Serbia has hosted the Eurobasket tournament in 2005.

Football

Serbia's national football team made their first appearance during the qualifying rounds for Euro 2008 although they did not qualify for Euro 2008. During the qualifying tournament for the World Cup 2010, Serbia won the first place in its group and consequently qualified directly for the 2010 World Cup Championship. Some members of the national team are international players such as, Nemanja Vidić, Branislav Ivanović, Miloš Krasić, Neven Subotić, and Nikola Žigić.

Serbian Superliga, is the highest professional league in the country. The 2008/2009 season champion was FK Partizan, followed by FK Vojvodina in the second place, and Red Star Belgrade in the third.

Tennis

Serbian tennis players Novak Đoković, Ana Ivanović, Jelena Janković, Nenad Zimonjić, Janko Tipsarević and Viktor Troicki are very successful and led to a popularisation of tennis in Serbia. Novak Đoković is the founder of an ATP tennis tournament, Serbia Open. Other well-known players are Monika Seles and Jelena Dokić.

Waterpolo

Serbia men's national water polo team is the reigning Water polo world champion winnig the 2009 World Championships in Rome, Italy. Yugoslavia national water polo team was twice the World Champion (in 1986 and 1991) and once the European Champion (1991). After becoming independent, Serbia have won three European Championships (2001, 2003 and 2006), finished as runner-up in 2008, won two World Championships (2005 and 2009) and won bronze medal at 2008 Summer Olympics held in Beijing.

VK Partizan won 6 titles of European champion and it is the second best European team in history of water polo.

Serbian capital Belgrade hosted the 2006 Men's European Water Polo Championship.

International rankings

| Organization | Survey | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Yale, Columbia University (at the World Economic Forum) | Environmental Performance Index[158] | 29 out of 163 |

| Institute for Economics and Peace [5] | Global Peace Index[159] | 78 out of 144 |

| Reporters Without Borders | Worldwide Press Freedom Index 2009 | 62 out of 175 |

| The Heritage Foundation/The Wall Street Journal | Index of Economic Freedom 2010 | 104 out of 179 |

| Transparency International | Corruption Perceptions Index 2009 | 83 out of 180 |

| United Nations Development Programme | Human Development Index 2009 | 67 out of 182 |

| Networked Readiness Index | Networked Readiness Index 2008–2009 | 84 out of 134 |

See also

- Outline of Serbia

- International rankings of Serbia

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies. This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ "REPUBLICKI ZAVOD ZA STATISTIKU - Republike Srbije". Webrzs.stat.gov.rs. http://webrzs.stat.gov.rs/axd/index.php. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Serbia". International Monetary Fund. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2010/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=64&pr.y=1&sy=2008&ey=2015&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=942&s=NGDP_RPCH%2CNGDP_D%2CNGDPDPC%2CPPPGDP%2CPPPPC%2CPCPIEPCH%2CLP&grp=0&a=. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ↑ "03". Zvrk.co.rs. http://www.zvrk.co.rs/Mskola/Istorija/srpskaistorija/srpskadespotovina/03.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500, By Jean W. Sedlar. Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=ANdbpi1WAIQC&pg=PA391. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "The Serbian Revolution and the Serbian State". Staff.lib.msu.edu. 2009-06-11. http://staff.lib.msu.edu/sowards/balkan/lecture5.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Parliament of the Republic of Serbia". Parlament.gov.rs. http://www.parlament.gov.rs/content/eng/o_skupstini/istorijat/istorijat1.asp. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/CLASS.XLS

- ↑ "Retailing - ANNOUNCEMENTS: Serbia in WTO by early 2010". SEEbiz.eu. http://www.seebiz.eu/en/corporate/retailing/serbia-in-wto-by-early-2010,42790.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Human development index trends, Human development indices by the United Nations. Retrieved on October 5, 2009

- ↑ "Map of Freedom in the World". freedomhouse.org. 2004-05-10. http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=363&year=2008&country=7548. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 http://www.becei.org/evropski%20forumi%20u%20pdf-u/Evropski_forum_No._4,_2008.pdf

- ↑ "Serbia submits EU membership bid". BBC News. 23 December 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8425407.stm. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ "Hrčak – Scrinia Slavonica, Vol.2 No.1 Listopad 2002". Hrcak.srce.hr. http://hrcak.srce.hr/index.php?show=clanak&id_clanak_jezik=14662. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Culture in Serbia - Tourism in Serbia, Culture travel to Serbia". Visitserbia.org. http://www.visitserbia.org/Culture-85-24-1. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "The Church of St. Apostles Peter and Paul". Panacomp. 2007-12-16. http://www.panacomp.net/content/view/133/206/lang,english/. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De administrando imperio. Vol. II, Commentary / by F. Dornik and others; ed. by R. J. H. Jenkins. London, The Athlone Press, 1962 (repr. 2006)

- ↑ A Short History of Russia and the .... Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=5NyQEh8qFIQC. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "File:Territorial expansion during the reign of Khan Krum (803-814).png - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia". En.wikipedia.org. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Territorial_expansion_during_the_reign_of_Khan_Krum_(803-814).png. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ The mountains of Montenegro - Google Böcker. Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=zDALl75839oC&pg=PA233&dq=viseslav&lr=&as_brr=3&hl=sv&sig=ACfU3U0azFv9hjdUTnknu-MqW6MzrqBURQ#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Srpsko Nasledje". Srpsko Nasledje. http://www.srpsko-nasledje.co.rs/sr-l/1998/03/article-06.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Mapof Frankish Empire

- ↑ "Fresco of King Mihailo". Njegos.org. http://www.njegos.org/medieval/mihailo.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "File:Servia1350AD.png - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia". En.wikipedia.org. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Servia1350AD.png. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Crucified Kosovo: Ljubisa Folic: Crucified Heritage". Rastko.org.rs. http://www.rastko.org.rs/kosovo/crucified/cr_heritage.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "CEEOL BALCANICA, Issue XXXVI /2005". Ceeol.com. http://www.ceeol.com/aspx/getdocument.aspx?logid=5&id=da7facf9c68246a7820bfdf1f9d9eaaf. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Rados Ljusic, Knezevina Srbija

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/g/glenny-balkans.html. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ↑ English translation: Leopold Ranke, A History of Serbia and the Serbian Revolution. Translated from the German by Mrs Alexander Kerr (London: John Murray, 1847)

- ↑ Royal Family. "200 godina ustanka". Royalfamily.org. http://www.royalfamily.org/ustanak/USTANAK_ENG.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Gordana Stokić (January 2003). "Bibliotekarstvo i menadžment: Moguća paralela" (in Serbian) (PDF). Narodna biblioteka Srbije. http://www.nb.rs/view_file.php?file_id=57.

- ↑ "Vladimir Corovic: Istorija srpskog naroda". Rastko.org.rs. http://www.rastko.org.rs/rastko-bl/istorija/corovic/istorija/7_8.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ L. S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453 (London: Hurst and Co., 2000), p. 248–250.

- ↑ Čedomir Antić (1998). "The First Serbian Uprising". The Royal Family of Serbia. http://www.royalfamily.org/ustanak/USTANAK_ENG.htm.

- ↑ "The Balkan Wars and the Partition of Macedonia". Historyofmacedonia.org. http://www.historyofmacedonia.org/PartitionedMacedonia/BalkanWars.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ http://www.cdsee.org/pdf/WorkBook3_sr.pdf

- ↑ "Typhus fever on the Eastern front of World War I". Montana State University.

- ↑ "The Balkan Wars and World War I". Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ↑ "Daily Survey". The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Serbia. 23 August 2004. http://www.mfa.gov.rs/Bilteni/Engleski/b230804_e.html.

- ↑ "Arhiv Srbije – osnovan 1900. godine" (in Serbian). http://www.archives.org.rs/.

- ↑ Saturday, 22 August 2009 Michael Duffy (2009-08-22). "First World War.com – Primary Documents – Vasil Radoslavov on Bulgaria's Entry into the War, 11 October 1915". Firstworldwar.com. http://www.firstworldwar.com/source/bulgariaatwar_radoslavov.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Највећа српска победа: Фронт који за савезнике није био битан (Serbian)

- ↑ Saturday, 22 August 2009 Matt Simpson (2009-08-22). "The Minor Powers During World War I – Serbia". Firstworldwar.com. http://www.firstworldwar.com/features/minorpowers_serbia.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Serbian army, August 1914". Vojska.net. http://www.vojska.net/eng/world-war-1/serbia/organization/1914/. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Tema nedelje: Najveća srpska pobeda: Sudnji rat: POLITIKA". Politika.rs. 2008-09-14. http://www.politika.rs/rubrike/Tema-nedelje/Najvecha-srpska-pobeda/Sudnji-rat.lt.html. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Тема недеље : Највећа српска победа : Сви српски тријумфи : ПОЛИТИКА (Serbian)

- ↑ "Fourth of Serbia's population dead". Pqasb.pqarchiver.com. 1918-06-30. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes/access/337249982.html?dids=337249982:337249982&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&date=Jun+30%2C+1918&author=PIERRE+LOTI.+Special+Contributor+to+%22The+Times.%22&pub=Los+Angeles+Times&desc=FOURTH+OF+SERBIA'S+POPULATION+DEAD.&pqatl=google. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ Asserts Serbians face extinction

- ↑ "Jewish Heritage Europe - Serbia 2 - Jewish Heritage in Belgrade". Jewish-heritage-europe.eu. http://www.jewish-heritage-europe.eu/country/serbia/serbia2.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ "Jewish heritage Europe". http://www.jewish-heritage-europe.eu/country/serbia/serbia2.htm.

- ↑ "Holocaust in Serbia". http://www.open.ac.uk/socialsciences/semlin/en/holocaust-in-serbia.php.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ustaša". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Britannica.com. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/620426/Ustasa. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ↑ primarily Syrmia region

- ↑ "Jasenovac". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005449. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ↑ Jasenovac Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

- ↑ http://www1.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%205930.pdf

- ↑ "LIST OF INDIVIDUAL VICTIMS OF JASENOVAC CONCENTRATION CAMP". JUSP Jasenovac. http://www.jusp-jasenovac.hr/Default.aspx?sid=6711. Retrieved 4 January 2010.